When I began applying for alt-ac positions instead of traditional faculty jobs, I soon realized that most of these jobs asked for a resume rather than a c.v. Given the variety in the ways that anyone structures their resumes and vitae, it was hard to know exactly how to make the changes to mine to reflect the expected differences between the two types of documents. Moreover, I’ve learned in the meantime that I’m not the only one with this problem! So I’m posting my c.v. and resume here as a sample for others who are applying for alt-ac careers, and welcome any feedback you might have on these or any examples in this vein that you would like to share.

First, here is my current c.v. [PDF]

You’ll see that I keep the formatting quite simple, with the following categories:

Current Position

Education

Teaching Areas

Dissertation

Articles and Book Chapters

Notable Online Publications

Awards, Fellowships

Talks & Presentations

Professional Activities

Even from these categories it might be obvious that I’m a non-traditional scholar–because of the unusual category of “Notable Online Publications.” I felt that it was important to have a place to mark my online work as well as my publication in print formats, so I chose to add this section to my c.v.

And now, here is my current resume [PDF], which I’ve used in applying for positions that are “alternative” to a traditional tenure-teaching path.

This is a much shorter document, and focuses on experience and skills rather than on awards and publications. It has the following categories, with the strongest emphasis being on my Technical Skills and on my work in the Digital Humanities:

Current Position

Education

Technical Skills

Recent Talks about Digital Humanities

Selected Professional Activities

One peculiarity on my resume is a lack of an employment history other than my current position. This is because I’ve had very little paid employment outside of my work as a TA or tutor. Generally this comes up in job interviews and I explain about being in graduate school and point to the various non-paying projects, such as hosting a podcast and serving on conference committees, that gave me important skills. Because I’ve only applied to jobs within the academy, this lack of employment history has not seemed to be much of a barrier. However, I suspect that if I were seeking employment in the “industry,” I might encounter more difficulties with not having had much work experience.

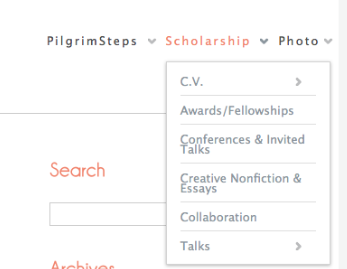

In addition to both of these documents, I also maintain an online portfolio at my janaremy.com domain name. This site breaks down some elements of my resume into more detailed categories and also offers hyperlinks to the various projects, conferences, and activities that I mention on my c.v. Though I don’t track my website analytics closely enough to know how often this has been consulted by hiring committees, I do get a few dozen hits on these pages on any given week, so it seems worth keeping this section of my portfolio updated regularly.

Screenshot showing the dropdown menu on my website.

Being still in the early stage of my career, I offer these examples with the caveat that they’ve been successful for me so far, but that I’m far from being an expert on what hiring committees are seeking from their applicants. And, I welcome links to your vitae and resumes in the comments below this post, as well as any feedback on my documents that you can offer.